Ghost Images of Earth

Aug. 5th, 2019 04:20 pmWhen going back to look up the video made by someone who had decoded the pictures on the “Voyager golden record” back from the audio signal they were converted to in 1977, I happened to turn up another video describing the process of turning sound into scanlines in some detail. While the process used there was more like that of the people who’d decrypted the first picture from Mariner 4 using numerical printouts, scissors, tape, and crayons, the video just happened to mention someone who’d written a program in Python such that nonprogrammers could feel like they were doing something themselves given the audio file. After turning up both the program and an audio file, I decided to see if I could sort things out myself.

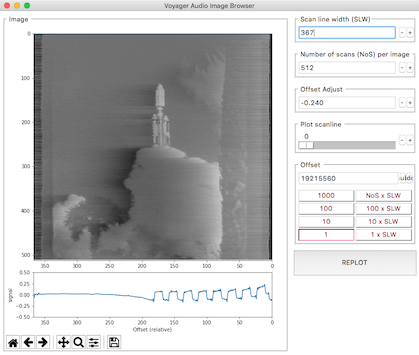

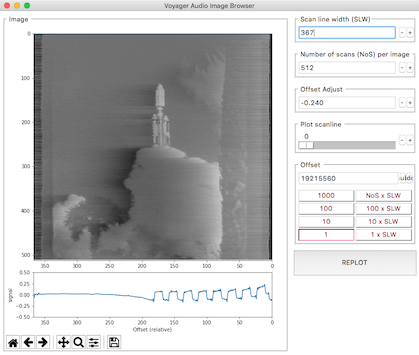

The program started more smoothly than some of my previous attempts to get Python working (it was a more complicated application, too), although when I loaded up the .WAV I’d made from one of the stereo tracks I got a screenful of static. It took me a while to figure out the programmer had used audio recorded at a much higher sample rate than what I had. Reducing the number of samples used to make up a scan line was a matter of trial and error, but all of a sudden I was looking at the “calibration circle” that leads off the pictures, however distorted. (Moving to each following picture in the track was, as the programmer had warned, a matter of making multiple adjustments.)

Hopefully, extraterrestrials that happen on one of the Voyagers will be able put a society’s collective intellect into not just decoding but enhancing the pictures; anyway, I’ve seen much better reproductions of the Voyager pictures myself. Still, the ghostliness of the images meant to preserve all of us is something in itself, and so is producing them, even if with a first boost from shared human knowledge, via a not-too-complicated method.

The program started more smoothly than some of my previous attempts to get Python working (it was a more complicated application, too), although when I loaded up the .WAV I’d made from one of the stereo tracks I got a screenful of static. It took me a while to figure out the programmer had used audio recorded at a much higher sample rate than what I had. Reducing the number of samples used to make up a scan line was a matter of trial and error, but all of a sudden I was looking at the “calibration circle” that leads off the pictures, however distorted. (Moving to each following picture in the track was, as the programmer had warned, a matter of making multiple adjustments.)

Hopefully, extraterrestrials that happen on one of the Voyagers will be able put a society’s collective intellect into not just decoding but enhancing the pictures; anyway, I’ve seen much better reproductions of the Voyager pictures myself. Still, the ghostliness of the images meant to preserve all of us is something in itself, and so is producing them, even if with a first boost from shared human knowledge, via a not-too-complicated method.